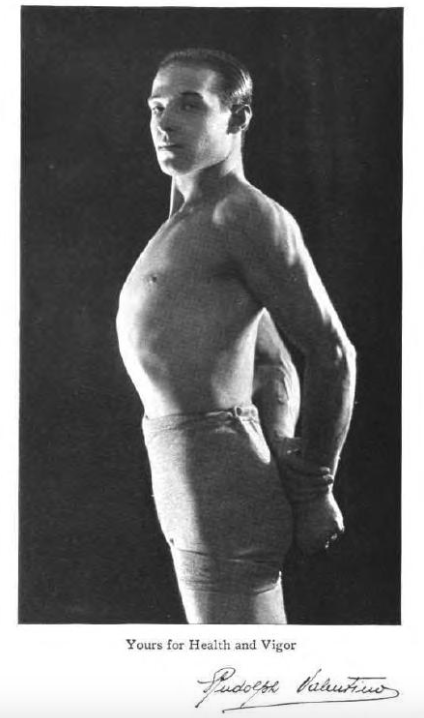

Would you like to know about silent screen star Rudolph Valentino’s workout? Of course you would!

In 1923, Valentino published an 81-page book of exercise tips called How You Can Keep Fit. I discovered this while searching for a photo I’d seen somewhere of Valentino in what seemed to be Chuck Taylors. (I am pondering the purchase of some Chuck Taylors.) And look, he is wearing them here! And they are very pristine!

Thanks to the Internet Archive, now you too can read and download the whole book.

An aside that is not really an aside: As a college frosh I took a seminar with the film scholar Miriam Hansen. Her class was where I first learned the phrase “the male gaze.” She talked about the way Valentino was marketed as the first sex symbol for women. Until him, men in the movies looked at women and women were looked at. But Valentino, who played exotic and oft-undressed sheiks and caballeros rather than all-American dudes, was himself presented as an object of desire. Of course, the natural order of things was SORTA kept: Women in his movies who looked lustfully at him were always bad women, while women he looked at were pure and good. But…women in the audience were, of course, looking at him! So let’s see, women who turn the female gaze on dudes are still bad, except maybe NOT, because Valentino is both subject and object. As Miriam wrote, “the erotic appeal of the Valentinian gaze… is one of reciprocity and ambivalence, rather than mastery and objectification.” It messes up the power structure. Which may be why male film execs and viewers often had major mishegas about Valentino. They impugned his masculinity and were obsessed with his sexuality. The fact that he was usually shot in the gleam-y, soft-focus-y way reserved for starlets worked men up into even more of a lather. But money talked, so moviemakers kept making movies in which he stripped, smoldered and shone. (Valentino, meet Magic Mike.)

But we were talking about his workout guide!

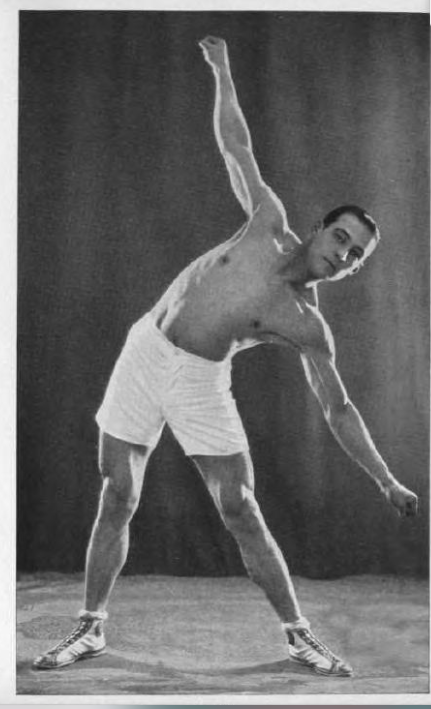

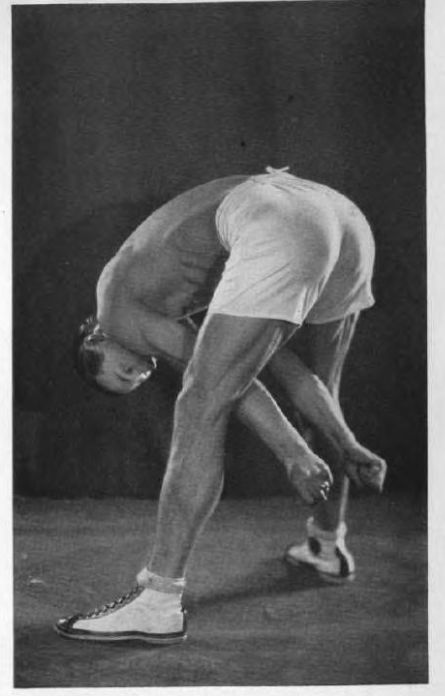

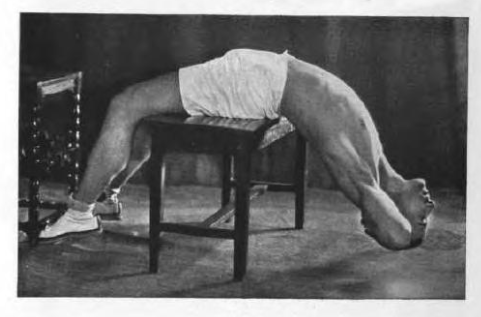

In Chapter III, which has the Flannery-O’Connor-esque title, “The Foundation of Strength Is a Good Back,” Valentino urges the reader to study Valentino’s lower spine. “You will note the conformation of these muscles as being especially rugged,” Valentino writes modestly.

Chapter IV is called “You Are Judged By Your Chest and Shoulders.” Valentino notes: “A narrow-shouldered man is not impressive. He is seen to be lacking in vigor at the very first glance. Likewise a flat-chested appearance is indicative of weakness. No one looks like a man unless he has a normal development of the shoulders and a full-chested aspect.” (To acquire this aspect, Valentino recommends supplementing the book’s exercises with chopping wood and pitching hay.)

Chapter IV is called “You Are Judged By Your Chest and Shoulders.” Valentino notes: “A narrow-shouldered man is not impressive. He is seen to be lacking in vigor at the very first glance. Likewise a flat-chested appearance is indicative of weakness. No one looks like a man unless he has a normal development of the shoulders and a full-chested aspect.” (To acquire this aspect, Valentino recommends supplementing the book’s exercises with chopping wood and pitching hay.)

Chapter V, “Let Your Abdomen Have the Strength of Iron Bands,” says, “Observe the average man of forty or upwards who has commenced to deteriorate and become flabby. The point at which he first gives evidence of becoming soft is in the region of the waistline, that is, the waistline in front.”

Chapter V, “Let Your Abdomen Have the Strength of Iron Bands,” says, “Observe the average man of forty or upwards who has commenced to deteriorate and become flabby. The point at which he first gives evidence of becoming soft is in the region of the waistline, that is, the waistline in front.”

From Chapter VII, “Better Eating for Harder Working”: “I never eat ice cream. For one thing, ice cream is too rich; for another thing, it is too cold; and finally in many cases you do not know what it is made of.” (Other than this bit of sadness, Valentino’s exotic-for-its-time advice to “eat as we did in my village in Italy” sounds surprisingly modern!)

From Chapter VII, “Better Eating for Harder Working”: “I never eat ice cream. For one thing, ice cream is too rich; for another thing, it is too cold; and finally in many cases you do not know what it is made of.” (Other than this bit of sadness, Valentino’s exotic-for-its-time advice to “eat as we did in my village in Italy” sounds surprisingly modern!)

Three years after the book was published, Valentino was dead at the age of 31. He died of a perforated ulcer. (Alas, his fitness advice on using abdominal exercises to prevent “rupture” does not seem to have worked.) Over 100,000 mourners, mostly women, thronged the street outside the church during his funeral. His girlfriend of a few months, actress Pola Negri, had a giant flower arrangement spelling out P-O-L-A placed next to the casket, and fainted fetchingly numerous times. But let us not let the man whom haters called “the pink powder puff” be remembered for his sad death, but rather for his glorious subversive beefcake-y life and legacy.