A new show at the Jewish Museum celebrates the children’s book master and civil-rights champion….and begs the question: Why do so few of us know he was Jewish?

But yes, Ezra Jack Keats was born Jacob Ezra Katz. He became one of the greatest children’s book illustrators ever, best known for his depiction of dilapidated urban landscapes that he somehow turned beautiful. “I love city life,†he once wrote. “All the beauty that other people see in country life, I find taking walks and seeing the multitudes of people (all the manifestations of people, one layer over another) and children playing.â€

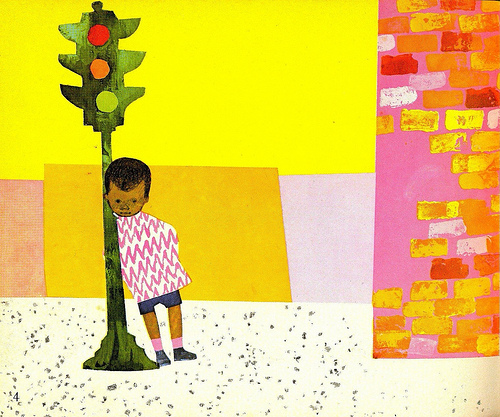

That description (“one layer over anotherâ€) evokes his own technique, combining vibrant bits of torn paper, thick smears of rich acrylic paint in brilliant colors, handmade marbleized paper, watercolor and pencil and snippets of pattern and ripped-up text and graffiti, all making visual poetry. (In a monograph about his work, the critic Brian Alderson called Keats a “mood explorer†rather than a storyteller.) This show honors the 50th anniversary of the publication of Keats’s Caldecott-medal-winning work The Snowy Day, which matter-of-factly featured an African-American protagonist – the first non-Sambo-esque, non-caricatured black child hero in mainstream American children’s literature.

When Josie was born, I received a board-book version of The Snowy Day as a gift. I opened it and was viscerally rocketed back to my own childhood experience of reading it. I’d loved the book’s evocation of the silence of a new snowfall, of the thrill of dragging a stick (a stick!) through untouched snow, the hilarity of a wad of snow falling – plop — on someone’s head. I’d loved the pattern on Peter’s pajamas and the fact that his family apparently had a pink bathtub. (A pink bathtub!) The Snowy Day was my first experience of loving art.

I’d surely noticed that Peter was black. But I easily projected myself into his experience, into the red snowsuit, into the tenement world so different from my own. Some critics have found that universality problematic; what makes Peter black, other than his skin? These critics felt that Keats was naively saying that humans are all alike; they thought the book lacked a meaningful depiction of the African-American experience. I think they miss the larger point that in 1962, a black hero in a children’s book for general audiences was groundbreaking. And The Snowy Day is absolute perfection on its own terms – a child’s solitary adventure in a big world. (Keats’s response to a critic who felt his characters weren’t identifiable enough as black: “Might I suggest armbands?â€)

Keats’s work is full of African-American, Latino and Asian characters, but he never once addressed Judaism. At first, I thought this fact made Keats an unlikely candidate for a Jewish Museum retrospective. But curator Claudia Nahson does a fine job of showing how Keats’s Jewish origins in East New York, Brooklyn affected his work and his interest in social justice. Still, what I find more interesting than what’s in the show is what isn’t. Reading the exhibit’s catalog gives you a better sense of the issues Keats didn’t address in his work; you get a fuller portrait of a man who seemed to wrestle with real ambivalence about being Jewish and who projected his experiences of poverty and discrimination onto children of other races without really delving into his own soul. Keats’ artwork is incredibly luscious, bright and beautiful; maybe he lacked the distance to see any loveliness in his own childhood.

The artist’s parents were poor immigrants; his mother’s 13-year-old sister died on her voyage from Poland in steerage. Jack Katz grew up in the slums of East New York. His parents apparently had a loveless marriage and were undemonstrative with their children; Keats wrote of feeling invisible, “walking around like a shadow.â€

A formative influence was the neighborhood junkman, whom everyone called Tzadik (righteous man). Tzadik is deracinated and transformed in Keats’s books into the gruff but loveable Barney. The real Tzadik was a lot scarier. In a notebook, Keats scribbled about this giant whose “red beard, bushy brows and massive head of fiery hair topped by a skullcap exploded around his face,†screaming at the kids of Vermont Street. Once Tzadik knocked him over and straddled him, yelling, “What’ll I do with these kids? They don’t know they’re Jews – they’re brainless. When have you done a good deed?â€

But one day, young Jack took a piece of wood Tzadik had dropped – Keats suspected that he might have dropped it on purpose, for him to pick up — and took it up to the tenement roof to paint on. Jack’s mother came up behind him, unnoticed, as he was making his first piece of original art; before that he’d always copied Honoré Daumier, a French painter of the underprivileged, and the illustrations in the Saturday Evening Post. (He also loved the work of Edward Hopper, the classic chronicler of urban loneliness.) According to the catalog, Jack’s mother touched his arm and said of the painting, “Maybe it will save you.â€

Jack replied, “Save me? From what?â€

“Oh I don’t know — maybe me,†she responded cryptically.

Keats wrote that it was the first time he could recall his mother touching him.

His art did save him from the ghetto, if not from sorrow. The catalog details his experiences with anti-Semitism in Paris, where he went to paint and study as a young man. He also worked as a muralist for the WPA and a “background man†(more invisibility!) for Captain Marvel at DC Comics. When he was beginning to seek work as a commercial illustrator in the late 1940s, he changed his name. His brother posited that he renamed himself because he was a fan of the poet John Keats, but his friend Esther Hautzig, author of The Endless Steppe (which, unlike Keats’s work, did address Jewishness and anti-Semitism autobiographically), said simply, “At Readers Digest he was advised that Keats would look better on the credits.†Was Keats merely doing what he had to to get jobs, or was he ashamed of his Jewish name? We don’t know. He never addressed the issue publicly.

But Keats was friendly with Isaac Bashevis Singer, and a carefully edited and rewritten 1971 letter in the show illustrates just how much Keats sweated over this relationship, carefully calibrating a relaxed but slightly obsequious tone. He wanted Singer to look at his (thus far) most autobiographical book, Apt. 3 (http://www.amazon.com/Apt-Picture-Books-Ezra-Keats/dp/0140565078), a tale of brothers in a dingy, dark, gray tenement whose world comes alive with color when they hear the music of a blind man playing a harmonica. Eventually Keats illustrated a story by Singer that was never published, for reasons unclear. Called The Slave, it was about Tobias, a poor Torah scribe, and his wife Peninah. Eventually fantasy author Lloyd Alexander saw and loved the paintings and wrote a new (and completely non-Jewish) story for them, The King’s Fountain.

More evidence (to me, anyway) of Keats’s oblique attempts to ameliorate his own suffering without delving too deeply into Judaism was his fascination with world religions. He did a book called God is in the Mountain in 1966, creating paintings to accompany quotations from the Bhagavad-Gita, the Qu’ran, the Upanishads, African proverbs, Greek verse, the work of Joseph Campbell and Lao-tzu, as well as a line from Rav Hillel. Again, Keats was looking for universality: “I am in every religion as a thread through a string of pearls,†was one of his Hindu selections.

Keats’s work did get more autobiographical as he got older, though. His (white) protagonist Louie was lonelier than Peter, more socially awkward, artistic, yearning to hug a puppet called Gussie — not-so-coincidentally his mother’s name. Keats went to Israel in 1982, shortly before his death. In his diary, shown in the exhibit, he wrote about how moved he was to place a note in the Western Wall. “I felt a strange state coming over me. An urgency to get the message through. Head covered, I placed my forehead against the cool wall and the palms of my hands against it. I was swept away. Overwhelming throbs of energy pulsated through me. Electrifying. This is the city where God came to life. I felt I stood before a strange eternity.â€

When Keats died, he was working on a story called “Where is God?†in which two children look everywhere. The unpublished book apparently concluded with one child saying, “I guess He’s everywhere.†The other child replies, “What makes you so sure God’s a He?â€

I’d like to think that had he lived a bit longer, Keats might have mined his Jewishness and his difficult childhood even more. But I don’t want to leave you with the thought that the show is a disappointment or a bummer. Keats’s work is so stunning, and in particular the gallery devoted to The Snowy Day is so gripping (and as always with the Jewish Museum’s children’s book art exhibits, the brightly painted reading corner with beanbag chairs is so pleasurable to sit and cuddle with a child and read in!) that the overall feel of the retrospective isn’t sad. The Snowy Day in particular is, I think, the perfect children’s book, the perfect blend of beauty, poetry, approachability and narrative. Peter’s quiet observation of the snowball fight of the “big boys†(and isn’t that just how little kids talk?) reminds us all – not just the artists among us – of watching life from the outside. Sherman Alexie, the National-Book-Award-winning author of The Absolutely True Adventures of a Part-Time Indian wrote, “I vividly remember the first day I pulled that book off the shelf. It was the first time I looked at a book and saw a brown, back, beige character – a character who resembled me physically and spiritually, in all his gorgeous loneliness and splendid isolation.â€

Gorgeous loneliness and splendid isolation describe Keats’s work perfectly. How sad that it described his own experiences.

A version of this piece ran in Tablet magazine.Â

[…] piece on the Ezra Jack Keats retrospective at the Jewish Museum of New York went up at Tablet magazine […]

[…] showed the students the Pete Cromer image as well as a collage by Eric Carle and one by Ezra Jack Keats for […]